Authentic Native American jewelry: how do you know if what you are buying is genuine?

You’re probably reading this because you are interested in purchasing authentic Native American jewelry. Perhaps you’ve heard that counterfeit Native American jewelry is endemic. Sadly, this is true. “It’s estimated that a staggering 50 to 80 percent of all jewelry marketed and retailed as ‘Native made’ in the U.S. is actually counterfeit—not made by a Native person.” *

A multi-year investigation by the Fish and Wildlife Service culminated in a felony conviction in 2017 of a dealer in New Mexico who had imported jewelry from the Philippines and sold millions of dollars of it as authentic Native American jewelry. This case is discussed in an article in Smithsonian Magazine online.**

A more recent case, still in the courts as of this writing, involved another group of individuals who were importing jewelry from the Philippines and selling it as authentic Native American jewelry: read the article on the Department of Justice website by clicking or tapping here.

There are several sad truths behind these cases of inauthentic Native American jewelry. First is the economic and cultural loss experienced by the tribes.

Some will call fake Native American jewelry “economic colonialization”. Generally, poor tribal populations have to compete with counterfeit goods that are imported from countries that have no connection with Native Americans and that have lower standards of living. This can drastically affect their ability for real Native American artists to earn a living using their cultural heritage. It also cheapens the perception of their work because consumers see counterfeit items being sold at much lower prices. In short, it is theft, both cultural and economic.

Southwestern Native American Jewelry

It is a terrible injustice to tribes everywhere, and Native American artists in the southwestern states are hardest hit because that is where the highest concentrations of fakes can be found. Native American jewelry lovers have been ripped off by dealers in what is considered the center of Native American jewelry, the city of Santa Fe, as well as in many other southwestern locations. Tourists as well as residents of these states have been victims of this counterfeit trade for many years.

How to Buy Authentic Native American Jewelry & Art

So what do you, the consumer, do to protect yourself, especially if dealers in New Mexico, the epicenter of Native American art, are dealing in counterfeit Native American art? One sure thing is to buy directly from a Native American artist, you might think. This is the case if you buy at shows that vet their participants and their credentials. However, buying Native American jewelry from someone on a street corner or a restaurant or a roadside stand is not a guarantee that they are the one who made it, as some people sell jewelry that was not made by them or is made with sub-standard materials.

Another option is to buy from a gallery/dealer with an established reputation. Home & Away Gallery, founded in the year 2000, buys 98% of its Native American jewelry directly from Native American artists with appropriate tribal credentials. We issue certificates of authenticity, so we stand behind everything we sell. We host Native American artists at the gallery for weekend trunk shows, so you will have the opportunity to meet them in person at the gallery in Kennebunkport, or at events we sponsor in other local venues.

Even when buying from a seemingly legitimate Native American jewelry store, the expression “buyer beware” still holds true. A strong indication of counterfeit jewelry is low pricing. I recall being in a Native American jewelry store in Albuquerque a few years ago and wondering how they could be selling authentic Native American jewelry at such low prices. The answer is they were not selling authentic Native American jewelry; they had been buying from one of the groups subsequently convicted of selling counterfeit work.

Just as with any type of research, ask questions. When buying from a retail outlet/gallery, ask the dealer how they know the work they sell is authentic. Do they know the artist, and did they buy the work from the artist directly? If they did not buy from the artist, what was the source?

Ask about the metals used in the jewelry. Is it stamped sterling silver or 14k? If not, how does the person know whether or the material is as represented? There are ways of testing metals that will determine if they are authentic Native American jewelry or not.

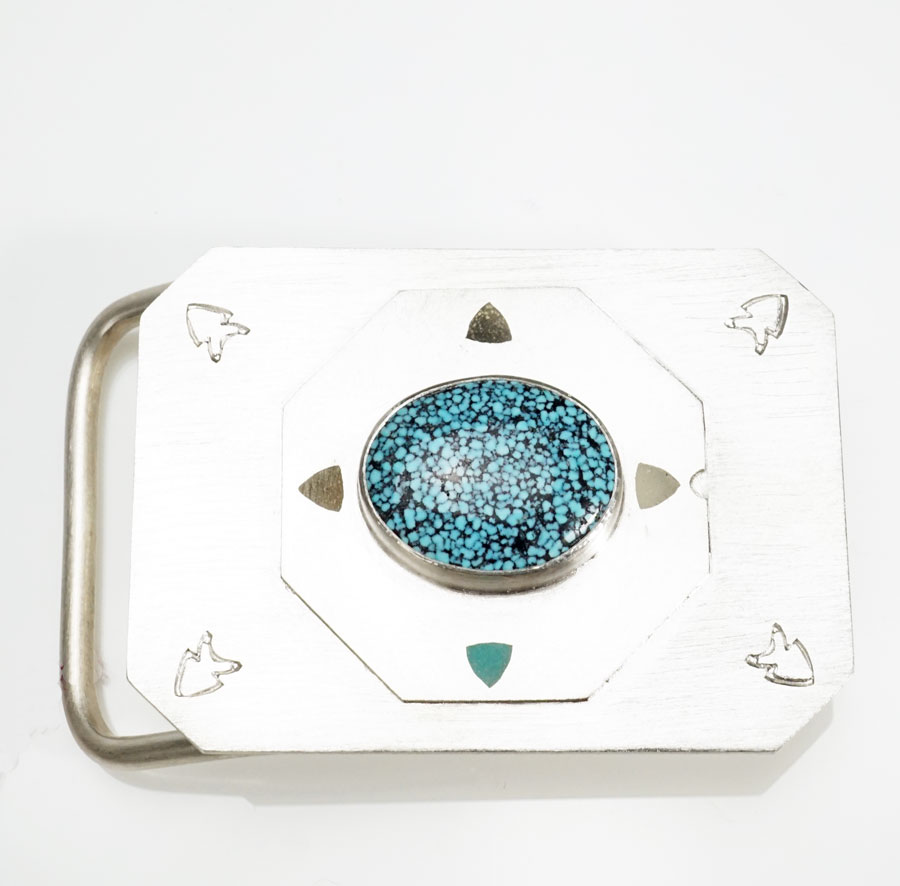

Determining Authentic Turquoise Native American Jewelry

Authenticity of turquoise is another enormous issue. Turquoise has been a mainstay of Native American jewelry for hundreds of years, if not millennia. Turquoise has been found at archaeological sites crafted into necklaces and earrings, sometimes using cottonwood or shell backing. While cottonwood is indigenous to the area, shells were often obtained in trade from coastal communities.

Today, with many turquoise mines in the U.S. having closed, some experts estimate that only 10% of turquoise used in Native American jewelry is natural. What does “natural” mean? In order for turquoise to be considered natural, it cannot have been altered in any way, other than being cut and polished.

There are numerous ways of altering turquoise. It can be dyed, stabilized, ground up and reconstituted, and more. It is against the law to sell turquoise as natural if it has undergone any of these processes. It is legal to sell turquoise that has been altered, provided the seller discloses the fact that it is not natural and does not label it as natural. The Santa Fe Reporter published an article in 2013 titled “How to Spy a Turquoise Lie”.

The SF Reporter article has a lot of valuable information for buyers. We take issue with one point in the article though: “Until the ’60s, or partway into the ’70s, there was no such thing as stabilized.” **** While modern techniques for stabilizing turquoise may have emerged as early as the 1950s, Pueblo artists have been stabilizing turquoise for many generations. Rather than epoxy, the artists used animal fats to stabilize the stone.

One thing to note is that the vast majority of turquoise beads used in necklaces are stabilized. Pueblo or other artists making heishi-sized-and-larger turquoise beads usually can’t afford gem quality stones. The natural turquoise stones available to them are typically too soft to be shaped and drilled, so they use stabilized turquoise. As stated above, it is legal to sell items made with stabilized turquoise, provided the seller does not try to pass it off as natural.

It can be very difficult for consumers to differentiate natural turquoise from stabilized turquoise. Lapidary artists can tell the difference when they cut into the stone, but even they are sometimes tricked by unscrupulous stone dealers, until they start cutting.

At times, stones that are not turquoise are dyed and passed off as turquoise. This is especially common with howlite. In its natural state, howlite is usually white with dark matrix. Because it takes dyes well, and because the matrix often resembles that found in many types of turquoise, dyed howlite is often deceptively marketed as turquoise. Jewelry containing dyed howlite can be spotted by a trained eye, but it can be difficult for consumers to do so. One indication to follow is the price. If the price seems too good to be true, it probably is.

With the scarcity of turquoise coming from American mines, some Native American artists are using stones from other countries. Stones from the Hubei mine in China are especially popular as of this writing. Do not be put off by Chinese turquoise per se, because Native American jewelry with turquoise from China can still have some very high-quality natural stones. The same guidelines apply to Chinese turquoise as to American turquoise: buy from reputable artists or dealers who present the source and type of turquoise honestly.

Native American Jewelry Federal Rules and Regulations

The U.S. Department of the Interior has jurisdiction over laws regulating trade in Native American goods, largely through the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. The act first came into being in 1935, and has continued to be amended throughout the years.

“The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 is a truth-in-advertising law. It is illegal to offer or display for sale, or sell, any art or craft product in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced, an Indian product, or the product of a particular Indian tribe.”***

There is a page on the Department of the Interior’s website allowing for the reporting of suspected sources of counterfeit work. The page also has several stories illustrating the widespread existence of such work:

“Example 1: Retail

During a business trip to New Mexico and Arizona, Harry W. went shopping for Indian jewelry for his girlfriend. Harry W. was impressed with what was offered at a gallery near his convention center hotel as outstanding “one-of-a-kind” “handmade” Indian jewelry by Michael L., which included silver, turquoise, jet, lapis, and other apparent precious stones. The sales clerk represented Michael L. as enrolled in one of the prominent New Mexico Pueblos and reported that he produced each piece from his studio workbench. However, as Harry W. traveled throughout New Mexico and Arizona, he continued to see enormous volumes of work attributed to Michael L. as “one-of-a-kind” “handmade” Indian jewelry. As a result, he became suspicious that the work was not made by one individual, but was being mass-produced. As the various sales clerks’ stories about Michael L. contradicted one another, Harry W. also began to suspect that the jewelry was not even Indian made.

“Example 2: Pow wow

Last summer, David B. and his family decided to attend a pow wow in the Midwest to experience Indian dancing, music, and craftwork first hand. After identifying a popular pow wow, David and his family attended the event where they purchased a number of items from a vendor’s booth, represented as Navajo rug weavings, Zuni inlay jewelry, and Hopi kachinas. For insurance purposes, David took the merchandise to a knowledgeable appraiser, only to find that the work was imported.

“Example 3: Internet

Sarah T. was a long-time collector of Alaska Native crafts. In searching the Internet one evening, she found a surprising selection of well-priced Alaska Native carvings, including wooden masks and totems and ivory figurines. She purchased the carvings and requested documentation for each piece. When the shipment arrived, she became suspicious of the carving documentation. Upon further inspection, she noticed a “Made in Bali” mark on the back of one of the masks, and areas on the other pieces that appeared to have country of origin markings removed.

“Example 4: Artist and Consumer

Mary B., an established potter enrolled in the Navajo Nation, has a friend who recently purchased a piece of pottery marketed as one of Mary B’s for a deep discount from a shop in another town. When the friend showed Mary B. the new purchase, Mary B. became very upset and told him that she had not made the piece of pottery. ” ***

If you suspect an individual or a retail store of selling non-authentic Native American jewelry or other items, the Department of the Interior would like to know about it. Click or tap here to read some stories and submit a suspected violation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

Home & Away Gallery Guarantees Authentic Native American Jewelry

We hope this blog post helps you figure out how to best approach Native American jewelry purchases. With vast amounts of counterfeit Native American jewelry being passed off as authentic, please be careful. Feel free to ask us about any of the turquoise or other materials we sell at Home & Away Gallery. We are happy to answer those questions, and we will provide you with a Certificate of Authenticity for everything you buy.

References:

* – New Mexico Magazine online: How to Buy Authentic Native American Jewelry, July 2019.

** Smithsonian Magazine online: Investigators Crack Down on Fraudulent Native American Jewelry.

*** DOI site with stories of counterfeit sales as well as a link to report counterfeit sources: https://www.doi.gov/iacb/act

**** “How to Spy a Turquoise Lie”